"Economic and social policy guidelines," under discussion

CUBA: Are the people the ones who decide?

13/12/2010

On December 1, the discussion before the Sixth Congress officially began in the organizations of the Communist Party of Cuba; the Congress will meet next April. The process "will include, until next February 28, all the union sections in workplaces and communities of the entire country" (Granma, December 1, 2010). The call to the Congress and the publication of the "Guidelines" for economic and social policy (see the note in La Verdad Obrera 401) opened a new scene on the island, by generating a process of political discussion at a national level.

Who decides?

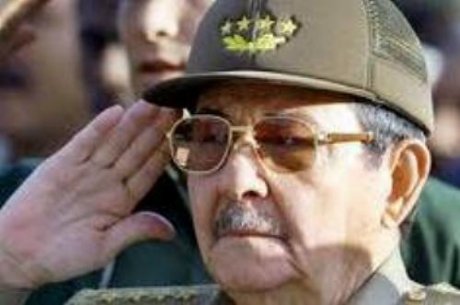

The December 1 Granma editorial is titled, "The people are the ones who decide," quoting Raúl Castro’s speech where he said on November 8, "The Sixth will be the Congress of all the activists and all the people, who will participate in the fundamental decisions of the Revolution."

Raúl and his team have been implementing a policy of reforms that in the "Guidelines" retrieve and intensify the measures initiated in the "special period" of the 1990’s, with new concessions to foreign capital, more autonomy in the management of public enterprises, and bigger spaces for the market and private initiative (independent workers, cooperatives, small businessmen, mixed enterprises), a policy of a strong restriction in state spending, by eliminating the "illegal gratuities" and other cuts in social services, and a campaign against "egalitarianism," with higher labor productivity and reducing the "bloated staffs," that, by April, will lay off half a million workers, displaced to the private sector.

In service to this course, the government has been trying out some political "tolerance." As the Cuban intellectual Pedro Campos describes (August 10, 2010, www.kaosenlared), it has been permitting "official criticisms of the paternalistic government, negotiations with the Catholic Church, a certain tolerance of criticisms, whether from revolutionary or oppositional positions, without open repression, recognition of sexual diversity, a relatively more open cultural policy and other policies, as long as they do not compromise the control of political power in the hands of the historic leadership".

The pre-Congress debate is registered in this direction as a relative, extremely controlled, "openness" (as has happened on other occasions), seeking to legitimize their economic plan among the population, to overcome the reluctance of groups of the bureaucracy and line up the leading strata behind their plan, and as a "safety valve" for unrest in view of a critical situation.

They are trying to hold a plebiscite on the government’s course and use popular support to settle internal differences, by preparing the road for a future Communist Party Conference (after the Congress) that would define a new direction. Raúl’s wing, supported by the FAR [revolutionary armed forces] (that control a key area of the economy) and by "technocratic" groups, and which has received Fidel’s backing, appears to collide with the reluctance of "ultra-conservative" wings of the bureaucracy that are afraid of being affected by the changes, or of other critical groups, even from the left.

The process is presented as a big expression of "socialist democracy"; however, it is being conducted under the firm bureaucratic control of the "single-party" regime and its plebiscitary methods, that deny the masses any real power of decision.

The "how" or the "what"?

Let us take two examples. Juventud Rebelde (of December 5) comments on the meeting of the Communist fraction at the José Martí Twist Tobacco Enterprise, belonging to the Grupo Tacuba, chosen as a representative example of the discussion process. The title illustrates how the debate is being guided: it is "the time for the hows in Cuban society." The whole description of the meeting stresses how to apply partial aspects of the plan: improvement of enterprise management and fulfillment of contracts, against "those who are lazy," who are obtaining social services without working, in favor of reducing social benefits branded as "illegal gratuities," etc.

Another note, this time from Trabajadores (December 5, 2010), representing the CTC [state-run Cuban unions], titled "With everyone’s voice," described as "an exemplary exercise of democracy," the meeting of the union section of services to workers, from the Unidad Básica of the Fructuoso Rodríguez contingent, where the central theme was "the priority that maintenance in all the buildings, the things done and things to be done, should have."

The CTC itself announced the dismissal of 500,000 workers in the coming months, "laying down the line" from above and guaranteeing its implementation, instead of developing a broad process of discussion among the ranks and defending the demands and interests that workers will express, facing the state.

In short, no fundamental discussion is being raised; rather, the program of the "Guidelines" is taken for granted, and the discussion is limited to the details of its application (the how). The crucial problem, prior to any solution, is excluded from the debate, as well as any fundamental balance sheet on the policy applied by the government in recent years. And, to be sure, neither the bureaucracy’s control of power nor their privileges appears in the list of topics, although one of most irritating and harmful evils is corruption among the leading strata.

The official plan entails enormous dangers for the Revolution and its gains; it affects the workers, and accentuates the decomposition of the nationalized economy on a road that, far from leading to "overcoming the errors and deviations in building socialism," aggravates the dangers of a gradual return, in the Chinese or Vietnamese manner, to capitalism and finally, to imperialist re-colonization.

This is the real background of a decisive discussion for the future of the Cuban Revolution, which would demand, therefore, the broadest workers’ democracy so that the workers can decide and take into their own hands the solution to the crisis.

The Church applauds the changes

But while the leadership is framing the debate under bureaucratic control and with their plebiscitary methods, by obstructing the possibility that critical tendencies on the left could develop and be organized among the workers or in the ranks of the Communist Party itself, it is letting groups run, like the Cuban Church, which is taking a side in the debate in order to "accompany the changes," because "today it is possible to express opinions much more easily than some years ago," and the official plan aims at "beginning to denationalize Cuban society." The priests intend "to help make the changes possible; there must be a positive attitude designed to present proposals capable of creating political trust, as well as widening and deepening the official plans." (Editorial from www.espaciolaical.org, from the Archdiocesan Council of the Laity of La Habana).

The government has been negotiating and making deals with the Church, that old and crafty Catholic counterrevolutionary party (as it was in Poland), by converting it into a tolerated, nationally visible, opposition, through which, as shown by the clergy’s role in the release and exile to Spain of imprisoned dissidents, they are negotiating with European and US imperialism (recently Archbishop Ortega went to New York). The Church and other pro-imperialist "dissident" groups are practicing demagogy in favor of the economic and political "opening," that imperialism would like to impose quickly, by seeking to capitalize on the lack of trade-union and political liberties and on popular dissatisfaction in view of material shortages. Contrast the attitude of the government that permits priests to act, give seminars, and every sort of activities to serve their political project, with their policy of silencing any voice from an independent left.

For the broadest democracy of the masses

The bureaucrats and some "Friends of Cuba" (read, "of the government") are trying to cover up for the policy of the Communist Party by discrediting critical positions from the left, if not with worn-out Stalinist slanders, then with the "argument" that, under the imperialist blockade and the serious internal difficulties, criticisms would weaken the Revolution. The opposite is true: the broadest debate is needed, radical criticism of the vital problems, in which all positions that raise economic and political alternatives to respond to the crisis, from the camp of the Revolution and the workers’ interests, should be able to be expressed widely.

It is necessary that the workers get the broadest democratic rights of discussion and organization, beginning with the right to present and widely disseminate (with full access to the public communications media, the government publishing houses, etc.) other platforms and programs alternative to the "Guidelines," the right to organize themselves to defend their platforms and programs, inside or outside of the Communist Party, and even to form union organizations to defend workers’ legitimate rights without government tutelage, and political tendencies (with the sole requirement that they be part of the anti-capitalist camp and of the defense of the Revolution).

In the debate, the fight for a program that, starting from the struggle against the blockade, will defeat the program of the "Guidelines," defend the gains of the workers, struggle against the bureaucracy and its privileges and propose the measures to redirect the nationalized economy in accordance with the needs of the working class and the transition to socialism, is posed. There cannot be real and revolutionary workers’ democracy without driving the bureaucracy from power, by achieving a regime based on workers’, campesinos’ and soldiers’ councils (or soviets) of freely elected delegates. Since Cuba’s future is inseparable from the development of the class struggle at an international level, that program must include the fight for the economic and political unity of the entire region in a Federation of Socialist Republics of Latin America.