10/31/2013 Washington Post

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner wins, but not by enough: Argentina post-election report

31/10/2013

By Julia Pomares http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2013/10/31/electoral-reforms-and-a-fragmented-party-system-argentina-post-election-report/

[Joshua Tucker: Continuing our series of Election Reports, we are pleased to welcome the following post-election report on the Oct. 27 Argentinian mid-term elections from political scientist Julia Pomares, Director of the Program on Political Institutions at CIPPEC.]

*****

On Oct. 27, Argentines went to the polls to renew half of the lower chamber of the national legislature and a third of the Senate. It was the last mid-term election before the end of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s second and last term in office. Although a challenger from Peronism obtained a landslide victory in the most important district (the province of Buenos Aires), Fernández succeeded in maintaining majorities in both chambers. However, this electoral result put an end to any attempt at constitutional reform to secure a third term for Fernández and shapes the scenario toward the 2015 presidential election in a highly fragmented party system.

Electoral reforms

Since the return to democracy in 1983, there have been few changes to the national electoral system – mainly, those introduced by the 1994 constitutional reform – but numerous reforms to other electoral rules. Over the last several years, every national contest came with an electoral innovation. In 2011, open primaries – compulsory for both parties and voters – were introduced, and they are now the only way to nominate candidates for all national offices. On the same day, all parties or coalitions of parties willing to compete must go to primaries. Even if the candidate is the result of an elite arrangement, her ballot needs to be there and she has to obtain 1.5 percent of the votes to get to the general election. This threshold tries to reduce the number of parties competing for the election. Argentina can boast of producing not only the best soccer players in the world, but also one of the largest party systems. At the moment of enactment of the law, 38 national parties and 659 district-level parties (who can compete for national legislators) were registered.

This 2013 election was not an exception and came with a new electoral reform. Argentina entered the small club of countries that lowered the voting age to 16. Young voters are given the right, but not the obligation to cast a ballot as the rest of electorate. This is so because of a practical issue rather than the outcome of an ethical debate: under-18s cannot be fined for not showing up to vote. Interestingly, a survey conducted by CIPPEC on the August primaries in Greater Buenos Aires showed that voters strongly support selecting candidates in primaries but do not favor youth vote.

What was at stake?

The lower chamber is elected from 24 multi-member districts for four-year terms and renewed by halves. The deputies are elected from closed party lists using the D’Hondt form of proportional representation. There is high variation in district magnitude – that is, the number of deputies elected from each district – ranging from five to 70. Moreover, Argentine lower chamber exhibits one of the most malapportioned electoral systems of the world. In the Senate, each district elects three members, two representing the majority, and one from the minority. They serve a six-year term and are renewed by thirds. Every two years, eight districts renew their seats.

Fernández’s party, the incumbent Frente para la Victoria (FPV), held a comfortable majority in both chambers. Because of the small number of seats that FPV had up for reelection, it was likely to keep the majority, even in the case of a bad election. However, the main issue at stake was whether the government would be able to secure a large enough majority in Congress that could provide the legitimacy to call (or pose a credible threat) for a constitutional reform that would allow Fernández to run for a third term. Yet, as the open primaries that took place on Aug. 11 anticipated, the results were quite different from what FPV was expecting.

The results

In a federal country with a fragmented party system, reporting national-level results of a legislative election is a tough challenge for a political analyst. And it is also deceiving since aggregate data hides important information about electoral strategies. Unlike Brazil, where the possibility of building different coalitions across offices was prohibited in 1998 (“verticalização de alianças”), in Argentina each party can decide its own strategy of alliances in each of the 24 districts. Both types of crossed alliances (across districts and offices) are allowed. That is why, for example, in the city of Buenos Aires, the right-wing PRO (the local incumbent) competed against anti-FPV peronist party and in other districts the two parties built a coalition to beat the FPV.

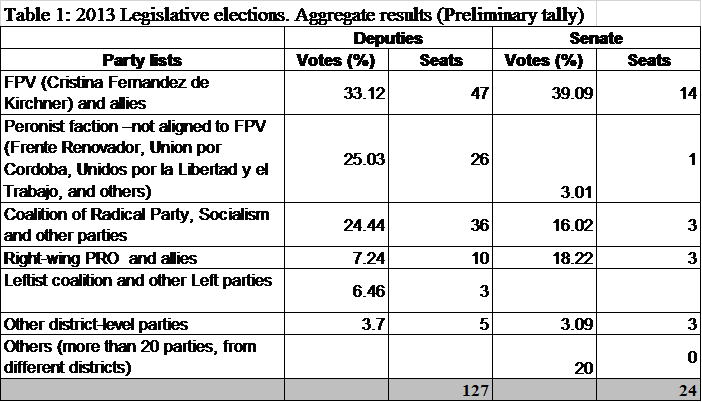

With this caveat in mind, the election results aggregated at the national level are as given below in Table 1.

Argentina Election Results (Table: Julia Pomares/The Monkey Cage)

The FPV got a third of the votes for both chambers and continues to be the largest bloc in both chambers. The Peronist coalitions challenging FPV (which include Mayor Sergio Massa’s electoral front and others) got 25 percent. The Radical party and allies got another 25 percent. Radicalism keeps the second largest bloc in the Senate. The Left showed a good electoral performance and succeeded in gaining three seats in the lower chamber.

However, if we take a look district by district, we get a different picture. The FPV lost the election in the four largest districts of the country: the province of Buenos Aires, the City of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe and Córdoba. In fact, in the last three districts, FPV ended up in the third place.

The main district of the country, the province of Buenos Aires, concentrates 24 percent of the electorate and received the largest media attention. Massa, a 41-year-old politician and former chief of Cabinet during Fernández’s first term in government, was the leading actor of the election. Now the mayor of a municipality in the Northern Greater Buenos Aires, he decided to compete against the FPV shortly before the primaries and took on board several powerful mayors of the Greater Buenos Aires previously aligned with the FPV. On the Sunday election, the FPV was hoping to replicate the results of the primary elections, which Massa had won by a margin of six points. Instead, Massa was able to double his margin of victory and got 44 per cent of the votes.

The road to 2015: Welcome to a normal (but not boring) country

If you don’t know anything about Argentina, you might still be thinking that this was an excellent election for the FPV. After 10 years in government (which included handling the effects of an international economic crisis), the incumbent party was capable of preserving the majority in both chambers, even with a president who has only two years left in office. But framing is a key part of politics, and these results ruined the government’s framing of the elections. After the landslide victory of Fernández in 2011 – 54 percent of the votes, the most striking presidential election since 1983 – some FPV leaders fueled the illusion that a plausible constitutional reform could give Fernández the possibility of a third term. With the current results in hand, the idea of a constitutional reform is completely buried. Moreover, three days before the election, the Supreme Court cancelled a gubernatorial election from a small district which would also have taken place this past Sunday. Claiming a very controversial interpretation of the recently reformed provincial constitution (which only allows for two terms in office), the governor was seeking a third term. The cancellation of the election was a signal to the other governors: unlimited reelection is off the table.

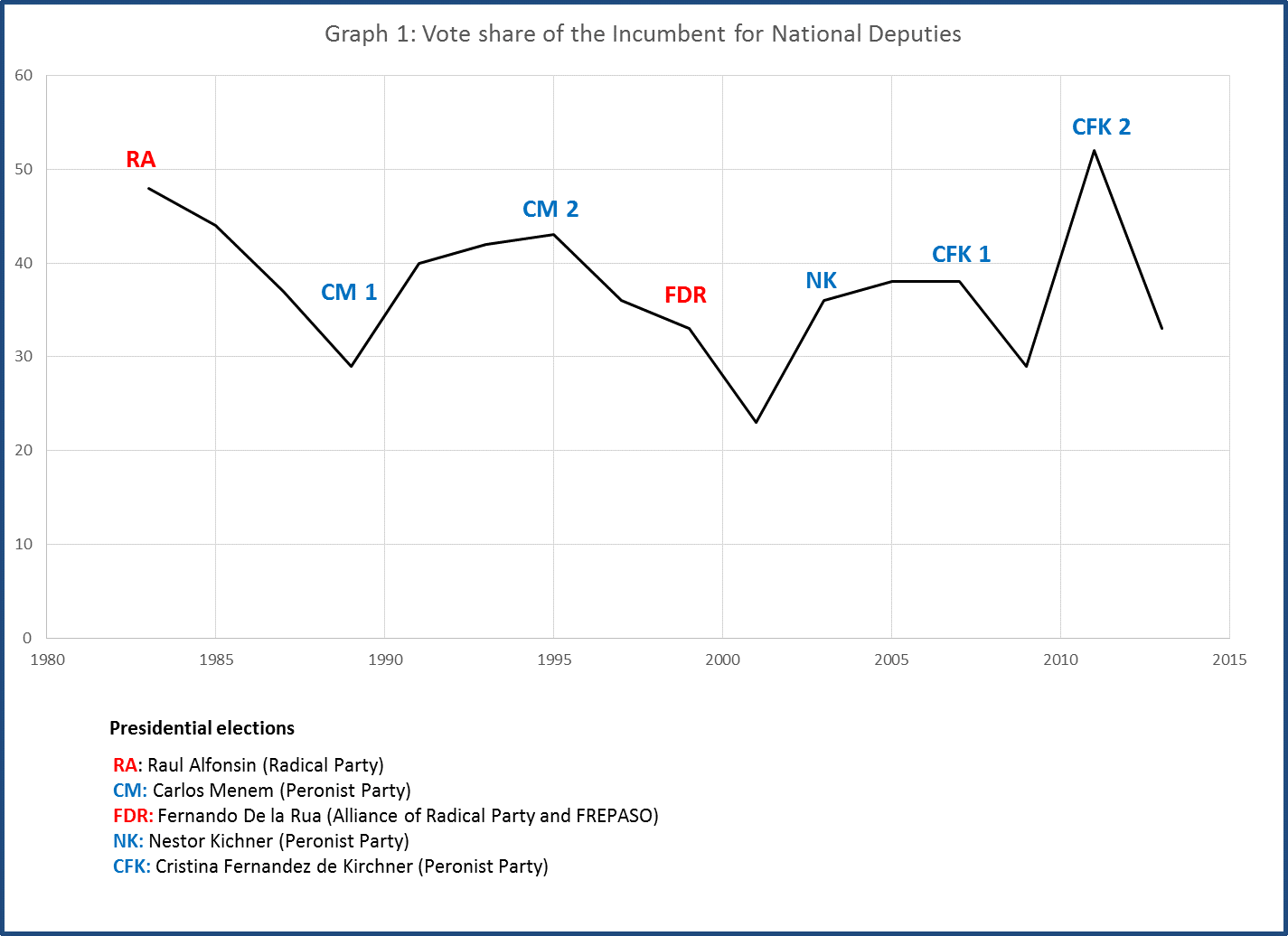

Since 1983, there was only one case of a mid-term legislative election before the end of the two-term presidential cycle. It was in 1997, before the end of Carlos Menem’s second term in government. The result was quite similar: The incumbent succeeded in maintaining control of the chambers but received a hard defeat in the province of Buenos Aires, anticipating alternation in 1999 (See Graph 1 below). However, the current party system is a very different creature from that of 1997. The level of party system fragmentation is higher and so is the level of intra-party fragmentation, especially within the Peronist party. In 1997, Menem was defeated in the province of Buenos Aires by a coalition of the Radical Party and a newly formed urban center-left party (FREPASO). In this 2013 election, it was a Peronist faction that defeated Fernández’s party, not only in Buenos Aires but in other districts as well. Along with Massa, several Peronist governors can be listed as the willing-to-be presidential candidates. Those better positioned seem to be willing to move the party to the right. Within the non-Peronist spectrum, there are also potential presidential contenders among those who garnered the victories in the large districts (Mendoza, Santa Fe and the City of Buenos Aires). The big test for the newly-introduced primaries might come in 2015. Will they be able to translate all these candidacies (especially within the Peronist camp) into stronger and fewer ones for the presidency?

Figure: Julia Pomares/The Monkey Cage

Other sources of uncertainty facing the country include the economy and the health of the president. Fernández had to go into surgery three weeks before the election and has been out of the political scene since then. The pace of her recovery is still unclear. Also, what will happen to the economy? Will the government continue the path to a more closed economy pursued over the last two years (which has not paid good electoral results)? A weak party system must be able to guarantee governance over the next two years and give way to a takeover in 2015. A tough and uncertain mission. But, there is one certainty: after 30 years of democracy, constitutional rules (well, and soccer) are the only game in town. Welcome to a normal country. But, not boring. Don’t worry.